On 2/3rds of a Day on a Plane, Finally

|

| My first plane to Japan |

Wednesday, June 23, 2010

International AirspaceOutside the Game:

I'm... not what you call a good flier under the best of situations. When you start up the day awaking with symptoms of a semi-recurrent throat infection a few hours before needing to get on a 14-hour plane ride, the situation is not significantly improved.

My plane was leaving at 11, my doctor's office didn't open until 9, and I was a less than happy camper. There is a new "immediate care" place that opened around the corner from me a few months ago, so I went there when it opened at 8. He said it may just be a sore throat, but in case it was the infection coming back, he gave me the necessary prescriptions to fight it, told me use them just in case, and sent me next door to the pharmacy to get them. All this was fine, it was only 8:30, and everything was going to be peachy. Just peachy.

Except that every single route to Newark airport was stopped cold. My father, who had the unfortunate privilege of driving me to the airport this day, said it was the worst traffic he had ever seen. I took this news rather well, and when I ran out of energy screaming, I called the airport to tell them I was running late and evaluate my options should I miss this flight. The options were not what one would call "good."

But eventually, everyone in front of us discovered there was a pedal next to the brake, and I managed to get to the airport twenty minutes before my plane boarded. Did I mention I had to check in at the airport? I got there at the same time as another gentleman in a similar situation. A member of the Continental staff scolded us quite sternly for being late, and then did the most astounding thing. They were helpful, expedited us through the line, and got us to security in under five minutes. You could have knocked me over with a feather. Security was also similarly painless, and I got to the gate in time to buy a book for the flight.

Ah, yes -- the flight. The longest I'd ever been on a plane previously was the eight hours it takes to get to Heathrow from the East Coast. By the end of that flight, I was ready to chew my arm off, and perhaps the arm of the person next to me. This was nearly twice that duration. Did I mention I twinged a back muscle running around in the airport with my rather heavy bag?

It wasn't all dire news. Because I booked the flight in January, I had managed to get my seat in the first row of Coach, which has extra leg room. I shared my row with a father and daughter going to visit relatives already in Japan. After some initial chit-chat before take-off, I did not speak to them for the entire trip.

As I was contemplating what I was going to do for the next 14 hours on the plane I found the entertainment system. Each chair now has individual on-demand entertainment channels for the entire trip, including movies, music, TV, and video games. (The system is Red Hat, by the way. I found this out when they had to reboot it about a quarter of the way through the flight to fix a hardware glitch with some of the consoles.) While this was reassuring, I realized that I could watch 8 regular Hollywood movies back-to-back, and I still wouldn't be in Japan yet. There was an unavoidable twinge at that realization.

Speaking of twinges, outside of a few small naps, my back was in such a state as to prevent any real sleep. I have actually forgotten all the movies I watched (although I started with How To Train Your Dragon, and ended with The Book of Eli [which I started to watch to see how bad it was, and then couldn't stop for the same reason]), and the endless TV shows. I even tried playing the video games, which were either universally crappy or unplayable.

We had a good deal of turbulence until we got to the North Pole, so food service was delayed. Because of the excitement to start the day, I didn't have breakfast, so by the time the first meal came through, I ate it in under a minute. There were two or three more little meals as the ride went on.

At the time I reached my absolute boredom limit, we were ten hours into the flight and not yet into Siberia, with about six hours left to go. I may or may not have gone crazy at some point. I don't remember a lot from this period clearly, but I did end up doing jumping jacks in the bathroom until I couldn't take it any more, and then went back to my seat to watch more Penn & Teller.

At some point, I had my moment of clarity. I either found the extra energy or gave up the last of my resistance and completely punched out for the remainder of the flight. It was like a runner's high for bored people. We actually got to the airport in Tokyo early, but just to twist the knife, we had to circle for a while until we got a landing slot.

However, the plane ride did, in fact, have an endpoint.

On Getting Where You're Going

|

| First stop, Narita Airport |

Thursday, June 24, 2010

Outside the Game:

This is when things just get a little... let's call it fuzzy, shall we? I'm going to label the start of this day as when I got off the plane in Japan. The fact that any impartial measure of time duration or date lines would indicate this is contra-factual, impartial measure can go jump in a lake.

So my day started as I got off the plane in Momma Nippon. I was at Narita Airport, which is not Tokyo proper. I had only my carry-on, so I didn't have to wait for my bags and went right to the security line. Those of you who remember my commentaries on the Midwest may remember the Midlands folk's predilection for lines. If Midwest America loves lines, the Japanese adore them in a way that's a little sexually inappropriate. The customs line was my first exposure to such things. It was a beautiful line by any estimation thereof, and well-managed. Not just the start and end were staffed, but seemingly random internal intervals also were managed by helpful staff. Cheery signs indicated your approximate wait time from the point of the sign, which gave it an idiosyncratic theme-park feel. At some point, I wondered if the roller coaster was going to be cool enough to justify the wait. But even though it was a rather lengthy, the wait wasn't oppressive buy any stretch of the imagination, and I was through in good enough time.

Once I was in the airport proper, I had to get to the Japan Rail office in order to activate my train pass. It was at this point, I learned the value of pointing. My faulting and mispronounced attempts at Japanese were appreciated, but the actual imparting of information went much smoother when I just pointed at my objective -- such as my Japan Rail voucher ("AH! Hai! Down two stairs. On right.") -- then my stumbling attempts to describe what I wanted in the native lingo.

I got to the office, read the signs, filled out the card they told me to fill out, and waited in another perfectly manicured line. It was here that I first ran into the "American flinch." It was what many Japanese do when they looked up and saw an American approaching -- a reflexive twinge that was hard to spot if you weren't looking for it. It wasn't mean-spirited by my estimation, but just a Pavlovian reaction to what they imagined was going to be a long transaction. Which is why I found if you make the mildest of efforts not to be a rampaging jerk, they really did seem to appreciate it. My attendant got me my pass, and when I asked if I could get my actual tickets for the trip now, he asked if I could wait for a half hour until it quieted down, clearly expecting an answer other than "yes." I confused him by agreeing and asking where the ATM was. When I got back a half hour later, the gentleman finished with the customer he was with, whisked me out of the short line, and got me all my tickets for the remainder of my trip.

My first hurdle was getting into Tokyo. Armed with the first of my tickets, I managed to completely fail to enter the train station without assistance. Upon entering, I found the track my train was on, and waited. When the train arrived ten minutes or so before departure, it was immediately swarmed by cleaning crews who went inside, put up little barriers so you wouldn't accidentally get on the train until it was suitably clean, and then scrubbed the train stem to stern in five minutes. The now-clean train was opened and boarded in another five minutes, and left promptly on time.

|

| The first of my many on-time trains in Japan |

If you haven't already guessed, this train experience was the complete opposite of anything you'll find in America. It was clean, efficient, quick, and quiet. All the stations and announcements are in Japanese, and then English. Once you get the hang of it, it is an extremely easy system to master. In under an hour, I was at my stop at Shinjuku, where I would be staying for the first three days.

Arriving at the station is one thing. Getting around anywhere, in a foreign county where you don't speak the language, and you're jetlagged as a jetlagged dog might be jetlagged, is quite another. I went to the JR Office in the station and helpfully pointed to the Google Map to my hotel that was completely in kanji and therefore useless to me. The attendant had to look up the address on her computer (which I didn't find particularly encouraging), had her "a-ha" moment, and gave me a helpful pantomime of the directions.

|

| Hey, look, kids: it's Japan. |

Filled with false confidence, I bounded out into Tokyo. The entirety of the route involved going in one direction and then turning once, so once I got the hang of how to cross the bloody street, I felt fairly certain I wouldn't die before I got there. This confidence was slowly chipped away as I couldn't seem to locate the giganto-huge sign for the hotel forty feet above my head. I checked in around 6 PM local time (WHATTHEHELLTIMEISITANDWHEREAMI PM in Oogie time), and then decided to wander off into the city, because, hey, why not?

I tried to keep it in straight lines and parallels so it would be easy to find my way back to the hotel, but I was so out of it that I didn't even think to ask for a map at the hotel, so my clever plan of easy backtracking didn't last very long. One thing I found was that even if you could completely see and comprehend some of the signs in Tokyo, it did not guarantee an actual understanding of the meaning. There was a sign that nearly all policemen had on their vests that, if forced to guess, I would have interpreted as "Do not turn invisible while tracking dirt everywhere while carrying a fancy light bulb on the edge of a platter." (Upon finding an English translation later, it turned out that it was an anti-smoking ad. So, I was close.)

|

| Seriously, what would your first guess have been? |

Shinjuku was a microcosm of huge buildings that can block out the heavens, with thousands of idiosyncrasies tucked inside them. Not more than a minute from my hotel, I found a large Shinto shrine complex and a meticulously manicured garden walk cut through a stockade of high-rises. Every easily-missed alleyway holds dozens of restaurants and stores that you wouldn't be able to find with a map and a guide, with even more of the same dug underneath street level as a counterpoint to the floors and floors of stores that rise to the sky around them.

|

| A shrine right in the middle of the city |

A lot of the first night was a blur of wandering around in a sleep-deprived state, in a place that was 1/3rds DisneyLand and 2/3rds Times Square. There are individual luminous moments of semi-dazed wanderings around a neon wonderland. I played pachinko for a good half hour. Under threat of law and a gun to my head, I could not tell you what exactly I did, if I scored well or not, or what was even going on at all, except that turning the handle shot balls up, and then there was lights and video. There was the giant crane machine in an arcade where the prize was a giant pot noodle. There were bunches of women dressed up like goth PowerPuff girls. It all blended together after a while in a harsh wash of nighttime neon and time-dilation.

At some point in my wanderings, I got found after being lost, and stumbled back, confused and unenlightened, to my hotel.

The Accommodations:

|

| Hotel Sunlite Shinjuku living up to its name |

For my first sojourn in Tokyo, I was staying at the Hotel Sunlite Shinjuku. As with many things in Tokyo, it is tucked off in an alley that you could pass fifty times without noticing (which may explain why the JR attendant didn't know it right away). The hotel was split in half across the alley, with a main office and an "annex" across the way that had the restaurant and more rooms. After confidently pointing to my reservation print-out, I was cheerily checked-in and given a wad of rules and regulations, ranging from not leaving the hotel with my room key, to what to do if there's an earthquake, or Godzilla attacks and there's an earthquake, or other such occurrences, most of which involving earthquakes.

I was also delivered the most important package of my trip. Waiting for me was an envelope from the good people at JapanBall, whom I had contracted to purchase all my baseball tickets for me. In retrospect, it was one of the smarter decisions on the trip, as I can't possibly imagine what the transactional exchange would have been like between myself and whatever unfortunate soul was working the ticket booth at the game that day. Actually, I probably could have eventually pointed and nodded my way through the ticket process, but it was one less thing to worry about as I trudged through just getting to the stadiums in question.

My room can only be described as "fun sized." On the right upon entering was a raised door that I found to led to my "fun sized" bathroom, consisting of a combo toilet-bidet (don't get those functions confused, kids!), and a combo sink/shower/tub that shared a single water supply. (It's really kind of hard to explain.) Further into the room was a small cabinet (with slipper holder), a desk built into the wall, a bed built into the other wall, a clock/radio/light control built into where the desk and bed met, and a TV stand built into the wall at the other end of the bed, just in front of a tiny refrigerator. The control panels would be a common feature in my hotels in Japan, and most featured very satisfying analog buttons that were fun to push. It was quite an efficient design, really. Laying on the bed for me was my complimentary cotton robe, and it was all I could do to wait until getting back from wandering around and getting cleaned up before putting on my robe and slippers and watching some TV.

The TV was a little hard to figure out, but if I had found the English translations for the remote quicker, I think the learning curve may have been less steep. Instead of the channel and volume being the up and down arrows right next to each other, it was the channel up/down for the regular TV right next to the channel up/down for the pay (read "porn") channels right next to each other, and the volume controls being below them. (Interesting side note: the machine to purchase cards for the pay channels for my floor was right outside my room, and there was no other reason to buy the cards except to use for adult movies, so there's no real "family-safe" reason to be at the machine. It made for a lot of awkward meetings as I left my room. "Oh, hello there. Would you look at that? I seem to be buying a porn card. And how are you today?") In addition to the regular and pay channels, there were some "wifi" channels that I never quite figured out. I pretty much left the TV on what I imagined was the sports channel, because it constantly showed yakyu and American baseball, as well as the World Cup games going on at the time.

The bed only had one pillow, but it was some odd bead-filled contraption from the near-future that managed to do the work of two. I'm still not entirely sure how that worked. I didn't sleep all that well the first night, and surprisingly enough, watching Japanese sports TV you can't actually understand at 4 in the morning is largely the same as watching it at 10 at night.

Smoking is sort of at a crossroads in Japan. There is a concerted effort to begin to phase it out, but it is still very much in the late 80s timeframe in America, with cigarette machines on every street corner and smoking sections available in nearly all restaurants (though I found that most ballparks had heavily ventilated "smoking rooms" or smoking areas that were the only places it was permissible to smoke), though they do take the precaution of putting up polite signs asking you not to smoke in bed.

An odd quirk of Japanese hostelry is that they generally ask you to turn in your guest key at the front desk if you are going out. I presume it is for some manner of security, but given the incredibly low crime rate and the fact that I felt safe walking around with my passport/ticket cozy hanging outside of my shirt, I don't know how much untoward stuff happens to tourists with their room keys with them. But then again, Americans are always creative.

On Watching Something that Both Was and Was Not Baseball

|

| Seibu Dome, 2010 |

Orix Buffaloes vs. Saitama Seibu Lions

Seibu Dome

Pacific League, Nippon Professional Baseball

Tokorozawa, Japan

16:00

Outside the Game:

I woke up in the morning not feeling well at all. Headaches, back pain, intestinal distress, hot and cold flashes, you name it. My main problem was that I didn't know how much of it was due to jetlag, not getting any sleep, medication-induced problems, or whether or not it was the plague. Another item adding to the confusion was that it was humid season in Japan. In addition to not feeling well, it was disconcerting to almost immediately break out into a full sweat upon hitting open air. I was initially not aware that this was an atmospheric phenomenon and not an internal one. Eventually, I noticed that most Japanese people carried around a towel. A towel is about the most massively useful thing an interstellar hitchhiker can have. In this case, they also provide a useful sop to the copious and nearly continuous sweat your body would be outputting through a given day. And the great thing about muggy is that it is not sunlight-dependent, so the sun going down didn't necessarily ensure any relief. Although I didn't feel all that well, I took a shot at the hotel breakfast buffet before heading out. I leaned heavily on the starches, ventured on some protein, and hoped for the best.

Undaunted, I decided to get in some sight-seeing before heading out for my first game in the evening. My hotel was located just north of Shinjuku Gyoen Park, established by an emperor as a fusion of Eastern and Western parks stylings. The main axis of the park was centered around a traditional Japanese garden, while other European styles, such as a formal French garden and an English country garden were laid out around it. Walking around it actually made me feel better, and the aesthetics of the thing were pretty extraordinary.

|

| Tranquility |

Having some more time to do touristy things before heading out to the game, I decided to navigate my way to the administrative area of the city, which was home to sky-reaching buildings of various size and ambitions, the largest of which being the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building, which also housed tourist observation decks. I took a ride up to one of the decks and got the 360 view of the city, made some very serious purchases at a toy store on the tourist deck, and then headed across the street to Shinjuku Central Park. The park was headed by a huge waterfall, and housed its own temple (undergoing renovations), and other more standard park-y features, such as children's play areas and athletic fields and the like.

|

| Tokyo, and a lot of it |

While the Japanese are generally fifteen minutes or so into the future, in some way the future is the past. For example, the caretakers at the park didn't use leaf blowers to clear the walkways; they used reed brushes that seemed to do the job very effectively without any power except muscle. Also, instead of sounding like a woodchipper grinding up woodchucks at deafening decibels, it made a relaxing "swooshing" noise when they raked.

|

| The future past |

It was election season in Tokyo, from what I was able to gather. There were the somewhat standard election posters all about, but there were other indicators as well. Campaigners on the street were giving out fans emblazoned with the smiling faces of their candidate of choice -- not that bad an idea in the stifling humidity that permeated at this time of year. A charming throwback to electioneering past was had with loudspeaker-equipped cars that drove around touting their candidate, and since this seemed rather popular method of vote-getting, it was not unusual to have cars backing several candidates chasing each other through the Tokyo streets, sometimes even talking to the opposition in the next loudspeaker car over. As with many things in Japan, it was just a quarter-turn away from what I'd define as normal.

I headed back to the hotel to wash up before the game, and turning on the sports channel by chance, I discovered that the Japanese have more baseball on per capita on regular broadcast channels than America can ever dream about. In addition to the Nippon Professional Baseball games that are broadcast in localities every night, every afternoon had broadcasts of MLB games, or at least the highlights from ex-Nippon League players. In the morning, the sports news was usually dominated by baseball (though Japan's run through the World Cup was also getting a great deal of press while I was there), so you can pretty much turn on the TV and watch baseball all day.

|

| All baseball, all the time |

Heading out to the stadium, I had a list of stops I knew I had to get to, a free pass to the use the train system, a vague idea of my destination... and that is pretty much it. As it turns out, this stadium was one of the most complicated destinations for my entire trip. This was a recipe for a disaster on an epic scale. For later excursions on this trip, I'd equip myself ahead of time with route maps, step-by-step directions, and even track assignments and train schedules, but for this day, I was armed with my ever-ready and devastating "Excuse me + Pointing" technique.

The problem with getting to the Seibu Dome was that I had to navigate two different train lines, and thanks to the fact that I was going at rush hour, I had also to take into account that certain trains were traveling express and not stopping at the station I needed for the exchange.

And frankly, I would have been still standing there at the station if not for the kindly attention of an engineer. He basically dragged me onto his train, got me to the exchange, dragged me to the other train, and told the new engineer to make sure the idiot gajin got off at the right stop and didn't end up in Okinawa. Here's to you, competent train employee willing to go above and beyond your job responsibilities. May your shining light of decency never extinguish.

|

| Seriously, this guy is my hero. |

Getting back after the game was a significantly easier endeavor, as I was playing the directions back in reverse, plus there were express trains set to get the crowd back from Tokorozawa to downtown Tokyo. Outside of the embarrassment of being in the same car with some loud, drunk ex-patriots (trying to communicate, "I'm not with them, and I'm sorry" with a wan grin is not as easy as you'd imagine), I got back to the hotel without incident, and settled in for a good two to three three hours of sleep before waking up with headaches and sundry aches. Lather, rinse, and repeat until morning.

The Stadium & Fans:

|

| Home plate to center field at the Seibu Dome |

The Seibu Dome was the first stadium I was seeing in Japan, and even then, I wasn't quite prepared for it. Once out of the train station proper, it empties out into a large, open "complex" for the team, most of it familiar to American fans. There were kids play areas, ticket booths, merch shops and the like. There were also kiosks for the fan club, which as far as I could tell were handled more like consumer loyalty programs than fan clubs proper in the US. You had a membership card, and could get "points" for being at the game and other such events, which presumably you could use for perks and the like. At many points, people were lining up to get something put on their fan club card. It is actually not a bad idea to engender some extra fan loyalty and might be worth exploring in America.

Then there were the merch shops for the opposing team, and that threw me for a loop. Stadiums in Japan have special shops set up for the visiting team, or all the other teams in the league, which would frankly be unheard of in America. But because of the presence of large number of opposing fans at every game, and I assume some manner of profit sharing, it makes sense to have it. In a turn of events that would likely have Marvin Miller spinning in his grave (if he was dead), the teams also use the players to merchandise concession food products as well as player merch. There were bento boxes and other specialty foods named after the players, graced by their smiling faces.

The final bit that would stick out to an American fan is the stage. As with most Japanese teams, one of the fixtures of the pre-game festivities is a show, usually performed by the cheerleaders and the mascots, usually aimed at the children in attendance. (Yes, yes, I know. Cheerleaders have no place in baseball, and my cultural tolerance only goes so far. Frankly, people to lead the cheers actually makes some sense in Japan, where the entire game is cheering by the fans, and having someone to lead said cheers is logical, but they don't actually do that, and the crowd cheers on their own, and the "cheerleaders" just dance around with the mascots.) What was particularly interesting is that the cheerleaders had to help set up the stage here, and I'm pretty sure "junior teamster" wasn't anywhere on their resume.

The stadium itself was also quite unique. A dome it was, but it was literally more of an umbrella over the entire structure than a single, sealed entity. The playing field was built into a depression into the ground, there was an open area between ground level and the dome, and then the dome covered the entire proceedings. It kept the rain out, let fresh air in, and presumably it was constructed just for that purpose, as opposed to say, Minute Maid Park or Chase Field, which were domed in for air conditioning so that patrons would not melt as much during July.

In a pattern to be found in most Japanese stadiums I visited, there was a strictly regimented access to different areas of the park. In most American parks, if you get to the park early enough, you can go to most areas of the facility (usually excluding the luxury boxes and other super-exclusive areas) to watch batting practice or solicit autographs at the home and visiting dugouts. This is mostly not the case in Japan, where your ticket will only gain you access to your immediate seating area, and, in some cases, the cheaper areas around you.

At the Seibu Dome, there was one entrance area in center field, and you could either go down the left field side (traditionally the "visiting team" section) or the right field side (traditionally the "home" section). There was one walkway at the top of the bowl in each areas, and from what I could see, the facilities and concessions were perfectly mirrored on each side. To progress toward home plate, you had to pass through a series of gates where you had to show your tickets: no ticket for an inner tier and you had to stay at whatever ring you were at. And even if, as with me, you had tickets right by home plate, the area directly behind home plate was a super-luxury area closed off from the other side of the ring, allowing you access to only half of the stadium.

Arrayed along the walkway were various concessions selling souvenirs and food (including what I would find to be the omnipresent Colonel of KFC). There were two specialty food areas, one open to everyone on the ring, and a "Lions Cafe" to which only people in the areas by home plate had access.

The seating itself comprised only one, extremely deep row of seating that circled the entire stadium. In the outfield cheering areas were two "picnic" areas without seats. The Seibu Dome also had what I would find to be a common feature at many Japanese stadiums: on-field seating. In the area just beyond the dugouts on either side of the field was a meshed in area off the foul line. The people sitting in this area got access to comfy chairs and batting helmets. (This frankly fit in with the general paranoia of Japanese baseball concerning foul balls.) The bullpens for either team lie on the other side of these on-field areas.

There was the standard jumbotron scoreboard out in center field, and a small ball and strikes board behind home plate. With few exceptions, there were no auxiliary scoreboards as you commonly find in MLB parks, and with few exceptions, the players' numbers weren't even displayed, just their positions. And, of course, everything was in kanji. It made for some interesting scorekeeping, let me tell you.

You may have also heard about the beer girls, and those stories are true. Diminutive Japanese women wander the stands proffering beer to all and sundry. At a command, they kneel down on the stairs by their customer, pour a cold one, and move on. There are other vendors who don't sell things slung on their back, but frankly, what's the point of that?

|

| They're real. |

As for the fans, this was my first exposure to a Japanese baseball game, and it was all rather new to me at the time. Once you get past the gender split at most Japanese games is easily an MLB executive drool-inducing 50/50, and that everyone at the game is watching the game, and not off shopping, or talking on their cell phone, or buying food, or whatever it is other people in America do at games, you can concentrate on the real differences. The fans, especially in the cheering sections, sing songs constantly throughout the game. When the home team is up, the home fans are singing. When the visiting team is up, the visiting team will sing. The songs are situational. Sometimes they will be directed to the player at bat, sometimes to the team in general, and it is always loud. Even the fans not singing will add to the noise with the ever-present thunder sticks, or just by clapping along. There can be some interaction between the two groups. If a batter that is being cheered makes an out, the opposing fans will sometimes jump in with a rhubarb (and one of them, I swear, is to the tune of "Shave and a Haircut, 2 bits.").

The cheering sections are the epicenter for this, with the home team in the right field bleacher areas and the visitors in the left field bleachers, usually. At the Seibu Dome, these areas were unseated "picnic" areas, so the cheering section had room to move. These aren't a slapdash group of screamers as you'd find in America, but organized teams, complete with flag bearers, drums, and trumpets. At its basic level, it is an impressive display, but when the organized drills get executed, with blaring trumpets, pounding drums, and flags and fans rising and falling to the rhythm, it is quite astounding. The stadium itself was about 2/3rds full this night, and the home team did have the advantage of numbers, so their cheering was a roar at times.

Their not having an overweight president, there is no seventh-inning stretch as Americans might identify it. In the break before the home half of the seventh, there is an event of sorts. As it was here (and as it was in most parks), the cheerleaders come out with the mascot and do a dance number before there is a singing of the team fight song. Then there may or may not be a t-shirt or ball giveaway (oh yes -- air canons have traversed the Pacific).

|

| Balloon launch |

Then there's the screaming condom launch. Stay with me here. At the top of the seventh inning, fans in their seats started to blow up balloons that, for lack of any better analogy, looked like brightly colored reservoir-tipped condoms. I'm willing to go with the flow, so I waited to see what happened. At the culmination of the seventh-inning festivities, there was a countdown, and everyone released those balloons, and they went screaming up into the night (making a whistling noise through a valve on the lip, I would find out), and then they all fell back to the ground. Everyone seemed to find this great fun, and I would discover that this was repeated at nearly every stadium I visited.

At the Game with Oogie:

|

| Ballpark grub |

My first meal at a Japanese park was teriyaki chicken and french fries at the club section Lions Cafe, which was thankfully air-conditioned. Sitting there with chopsticks in hand, looking over the ballfield, I had a real moment of disconnect wondering what in the hell was going on here.

I was sitting next to a couple of Japanese women with some high-end photography equipment who apparently came to just to get really good pictures of their favorite players. I don't even think they knew I was there.

The Game:

|

| Celebrating a home dinger |

I could go into all of the ways that yakyu is different from baseball, but it is a topic of sizable enough scope that I'm probably going to spin it off into it's own article. The short version is that the Japanese ball (that I saw at least) had it's closest approximation in the late 70s/early 80s NL model: ultimate small ball. Speed, defense, and precision pitching, instead of station-to-station, power, and fireballers. It was quite a refreshing change from how stagnant even modern NL ball had gotten. All you really need to know is that in the third inning, the leadoff batter got on for the home team, and the next batter successfully sacrificed him over with a textbook bunt on the first pitch, and the crowd lost its frigging mind cheering. You ain't in Kansas any more, Dorothy. (And this was the more "progressive" Pacific League, which has the designated hitter rule.)

Hell, you didn't even need to get into the game proper to know you weren't at home. For ceremonial first pitches, they generally bring out the entire team, have the mascot as an umpire, and actually have the leadoff hitter for the opposing team stand in for the pitch. If that wasn't different enough, the first pitch this evening was to be delivered by a school-age little boy. My expectations for a shot put that may or may not reach the plate were shattered as the tyke dug in on the rubber and snapped off a breaking ball that looked like it fell off a table ten feet high. Kansas? I'm not sure I'm still on the damn planet.

The two teams and players are announced, and the home team is brought out onto the field through a gauntlet of cheerleaders and mascots. Sometimes they will toss giveaways to the crowd as they come out to the field. The national love for karaoke is indulged with the playing a team fight song, with a sing-along provided by the scoreboard. I can guarantee you that none of the fans needed any prompting for the words.

The game did veer back to familiar territory with the playing of the (completely unfamiliar) national anthem. Even more curious was the fact that all the teams didn't do so. (I think it was just the Pacific League teams that did.) Less a fixture of the Japanese game, I imagine, by why some do some don't remains a mystery to me.

Many of you probably heard how there is a premium in Japanese games for scoring first. It isn't even just scoring first, but getting the first hit. There's a point of pride to it that the cheering sections of each time will go to for the rest of the game. In this case, the visiting Buffaloes got both in the top of the second, bringing two runs across on a leadoff hit batsman and a homerun to right field. But that was about it for the Buffaloes. Outside of a run in the sixth (brought across with a leadoff double, fielder's choice, and sacrifice fly), the Lions' Wakui shut them down completely, going the full nine in the win. The Lions got the lead when the aforementioned sacrificed runner scored on a single, and then back-to-back homers followed in the third. (Japanese players on the home team who hit a home run are generally rewarded by the team mascot with a giant stuffed animal of the mascot upon their return to the dugout. I am sure I do not know why.) The Lions brought additional single runs across in the 4th and 5th respectively, giving the Lions and Wakui all they needed for a 7-3 win.

After the victory, I saw my first instance of a Japanese innovation that is just making it over to American shores: the on-field player-of-the-game ceremony. As soon as the last out is recorded in a home-team victory, teams of workers scurry onto the field and construct a broadcast platform, from which the player of the game is interviewed on the field, and the interview is broadcast on the main scoreboard. Most all of the home fans stay until this broadcast is completed (assuming the home team wins, of course).

The Scorecard:

|

| Buffaloes vs. Lions, 06/25/10. Lions win, 7-3. |

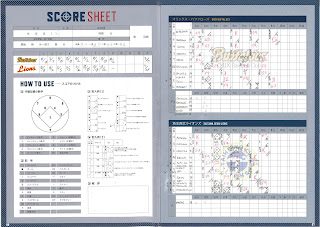

I had been told that most Japanese teams don't have scorecards as part of their programs, so it was probably just dumb luck that I picked one that did for my first game of the trip. The scorecard was part of a half-sized magazine-style program that ran about $2.25.

The scorecard proper was divided up into one page of directions and summaries, and one page of the scorecard itself. Nearly all of the instructions and summary information was written in kanji, but I knew enough about scorecards to work out the main event pretty well, even their odd little way of tracking balls and strikes.

Now the scoreboards in Japan don't use romanji most of the time, nor did they display the player numbers (just their position). This made an additional level of effort to keeping score. I had purchased a copy of the English Japan League guide, so I had all the lineups and rosters in kanji and romanji, but it was an extra step to work out what kanji player was on the scoreboard, look him up, and then update the scorecard in English. That, plus not knowing what the hell the PA person was announcing made it all the more difficult to follow along. Fortunately, having such good seats, I was able to see the players close-up and in the on-deck circle, so I could at least keep track of numbers and names that way. Outside of having no kanji translations for the umpires (which weren't provided in the book), and still not knowing what the summation categories are yet, I was able to keep a complete scorecard.

The Accommodations:

I was staying at the Sunlite for the entirety of my first Tokyo trip. After a night of something resembling sleep, I went downstairs and had the breakfast buffet, which was half Western-style (cereal, sausage, eggs, bacon. etc) and half Japanese style (rice, miso, salad, fish). I mixed and matched a little, not knowing if it was going to stay resident in my system for any great lengths of time anyway, and then went back up to my room to get ready to go out.

When I got back to my room after my morning and early afternoon outings, I found a curious thing upon returning to the room. The room service people didn't just clean around my stuff as per the usual (at least in America) procedure. They completely re-arranged my stuff. And here's the thing: they were right. I wasn't using the special shelf or the toiletry bag that they had put there for that purpose, my luggage didn't belong where it was, and a dozen other little adjustments that made the entire arrangement much better. So go figure.

2010: Japan I

No comments:

Post a Comment